In October, 1944, at age eighteen, I was drafted into the U.S. army. Largely because of the "Battle of the Bulge," my training was cut short. My furlough was halved, and I was sent overseas immediately. Upon arrival in Le Havre, France, we were quickly loaded into box cars and shipped to the front. When we got there, I was suffering increasingly severe symptoms of mononucleosis, and was sent to a hospital in Belgium. Since mononucleosis was then known as the "kissing disease," I mailed a letter of thanks to my girlfriend.

By the time I left the hospital, the outfit I had trained with in Spartanburg, South Carolina was deep inside Germany, so, despite my protests, I was placed in a "repo depot(replacement depot). I lost interest in the units to which I was assigned and don't recall all of them: non-combat units were ridiculed at that time. My separation qualification record states I was mostly with Company C, 14th Infantry Regiment, during my seventeen-month stay in Germany, but I remember being transferred to other outfits also.

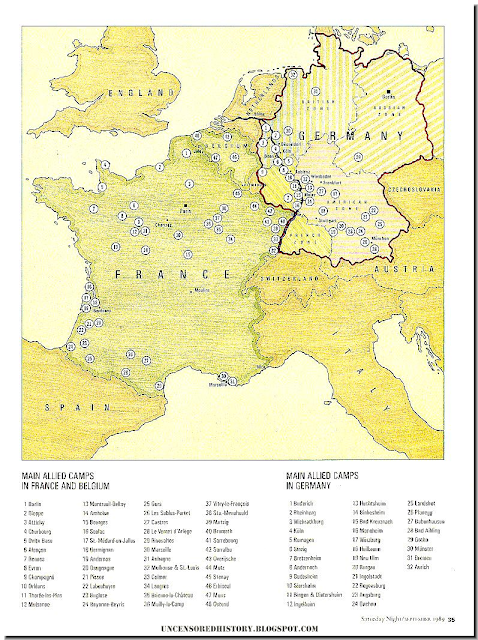

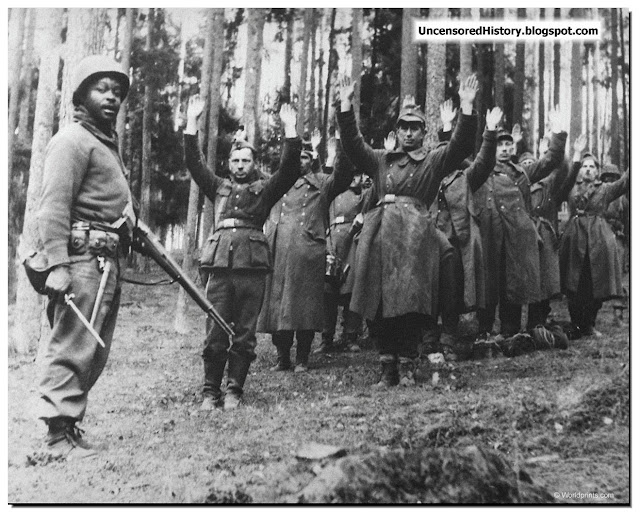

In late March or early April, 1945, I was sent to guard a POW camp near Andernach along the Rhine. I had four years of high school German, so I was able to talk to the prisoners, although this was forbidden. Gradually, however, I was used as an interpreter and asked to ferret out members of the S.S. (I found none.) In Andernach about 50,000 prisoners of all ages were held in an open field surrounded by barbed wire. The women were kept in a separate enclosure I did not see until later. The men I guarded had no shelter and no blankets; many had no coats. They slept in the mud, wet and cold, with inadequate slit trenches for excrement. It was a cold, wet spring and their misery from exposure alone was evident. Even more shocking was to see the prisoners throwing grass and weeds into a tin can containing a thin soup. They told me they did this to help ease their hunger pains.

Quickly, they grew emaciated. Dysentery raged, and soon they were sleeping in their own excrement, too weak and crowded to reach the slit trenches. Many were begging for food, sickening and dying before our eyes. We had ample food and supplies, but did nothing to help them, including no medical assistance. Outraged, I protested to my officers and was met with hostility or bland indifference. When pressed, they explained they were under strict orders from "higher up." No officer would dare do this to 50,000 men if he felt that it was "out of line," leaving him open to charges. Realizing my protests were useless, I asked a friend working in the kitchen if he could slip me some extra food for the prisoners. He too said they were under strict orders to severely ration the prisoners' food and that these orders came from "higher up." But he said they had more food than they knew what to do with and would sneak me some.

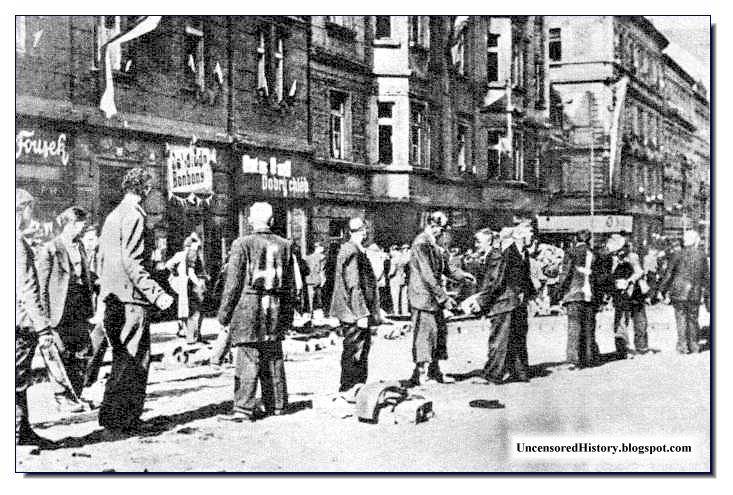

(Click on image to enlarge it)

When I threw this food over the barbed wire to the prisoners, I was caught and threatened with imprisonment. I repeated the "offense," and one officer angrily threatened to shoot me. I assumed this was a bluff until I encountered a captain on a hill above the Rhine shooting down at a group of German civilian women with his .45 caliber pistol. When I asked, Why?," he mumbled, "Target practice," and fired until his pistol was empty. I saw the women running for cover, but, at that distance, couldn't tell if any had been hit. This is when I realized I was dealing with cold-blooded killers filled with moralistic hatred.

They considered the Germans subhuman and worthy of extermination; another expression of the downward spiral of racism. Articles in the G.I. newspaper, Stars and Stripes, played up the German concentration camps, complete with photos of emaciated bodies; this amplified our self-righteous cruelty and made it easier to imitate behavior we were supposed to oppose. Also, I think, soldiers not exposed to combat were trying to prove how tough they were by taking it out on the prisoners and civilians. These prisoners, I found out, were mostly farmers and workingmen, as simple and ignorant as many of our own troops.

As time went on, more of them lapsed into a zombie-like state of listlessness, while others tried to escape in a demented or suicidal fashion, running through open fields in broad daylight towards the Rhine to quench their thirst. They were mowed down.Some prisoners were as eager for cigarettes as for food, saying they took the edge off their hunger. Accordingly, enterprising G.I. "Yankee traders" were acquiring hordes of watches and rings in exchange for handfuls of cigarettes or less. When I began throwing cartons of cigarettes to the prisoners to ruin this trade, I was threatened by rank-and-file G.I.s too.

The only bright spot in this gloomy picture came one night when.I was put on the "graveyard shift," from two to four A.M. Actually, there was a graveyard on the uphill side of this enclosure, not many yards away. My superiors had forgotten to give me a flashlight and I hadn't bothered to ask for one, disgusted as I was with the whole situation by that time. It was a fairly bright night and I soon became aware of a prisoner crawling under the wires towards the graveyard. We were supposed to shoot escapees on sight, so I started to get up from the ground to warn him to get back.

Suddenly I noticed another prisoner crawling from the graveyard back to the enclosure. They were risking their lives to get to the graveyard for something; I had to investigate. When I entered the gloom of this shrubby, tree-shaded cemetery, I felt completely vulnerable, but somehow curiosity kept me moving. Despite my caution, I tripped over the legs of someone in a prone position. Whipping my rifle around while stumbling and trying to regain composure of mind and body, I soon was relieved I hadn't reflexively fired. The figure sat up. Gradually, I could see the beautiful but terror-stricken face of a woman with a picnic basket nearby. German civilians were not allowed to feed, nor even come near the prisoners, so I quickly assured her I approved of what she was doing, not to be afraid, and that I would leave the graveyard to get out of the way. I did so immediately and sat down, leaning against a tree at the edge of the cemetery to be inconspicuous and not frighten the prisoners. I imagined then, and still do now, what it would be like to meet a beautiful woman with a picnic basket, under those conditions as a prisoner. I have never forgotten her face. Eventually, more prisoners crawled back to the enclosure. I saw they were dragging food to their comrades and could only admire their courage and devotion.

On May 8, V.E. Day, I decided to celebrate with some prisoners I was guarding who were baking bread the other prisoners occasionally received. This group had all the bread they could eat, and shared the jovial mood generated by the end of the war. We all thought we were going home soon, a pathetic hope on their part. We were in what was to become the French zone, where I soon would witness the brutality of the French soldiers when we transferred our prisoners to them for their slave labor camps. On this day, however, we were happy. As a gesture of friendliness, I emptied my rifle and stood it in the corner, even allowing them to play with it at their request! This thoroughly "broke the ice," and soon we were singing songs we taught each other or I had learned in high school German ("Du, du liegst mir im Herzen"). Out of gratitude, they baked me a special small loaf of sweet bread, the only possible present they had left to offer. I stuffed it in my "Eisenhower jacket" and snuck it back to my barracks, eating it when I had privacy. I have never tasted more delicious bread, nor felt a deeper sense of communion while eating it. I believe a cosmic sense of Christ (the Oneness of all Being) revealed its normally hidden presence to me on that occasion, influencing my later decision to major in philosophy and religion.

Shortly afterwards, some of our weak and sickly prisoners were marched off by French soldiers to their camp. We were riding on a truck behind this column. Temporarily, it slowed down and dropped back, perhaps because the driver was as shocked as I was. Whenever a German prisoner staggered or dropped back, he was hit on the head with a club until he died. The bodies were rolled to the side of the road to be picked up by another truck. For many, this quick death might have been preferable to slow starvation in our "killing fields." When I finally saw the German women in a separate enclosure, I asked why we were holding them prisoner. I was told they were "camp followers," selected as breeding stock for the S.S. to create a super-race. I spoke to some and must say I never met a more spirited or attractive group of women. I certainly didn't think they deserved imprisonment. I was used increasingly as an interpreter, and was able to prevent some particularly unfortunate arrests.

One rather amusing incident involved an old farmer who was being dragged away by several M.P,s. I was told he had a "fancy Nazi medal," which they showed me. Fortunately, I had a chart identifying such medals. He'd been awarded it for having five children! Perhaps his wife was somewhat relieved to get him "off her back," but I didn't think one of our death camps was a fair punishment for his contribution to Germany. The M.P.s agreed and released him to continue his "dirty work." Famine began to spread among the German civilians also. It was a common sight to see German women up to their elbows in our garbage cans looking for something edible -- that is, if they weren't chased away. When I interviewed mayors of small towns and villages, I was told their supply of food had been taken away by "displaced persons" (foreigners who had worked in Germany), who packed the food on trucks and drove away. When I reported this, the response was a shrug.

I never saw any Red Cross at the camp or helping civilians, although their coffee and doughnut stands were available everywhere else for us. In the meantime, the Germans had to rely on the sharing of hidden stores until the next harvest.

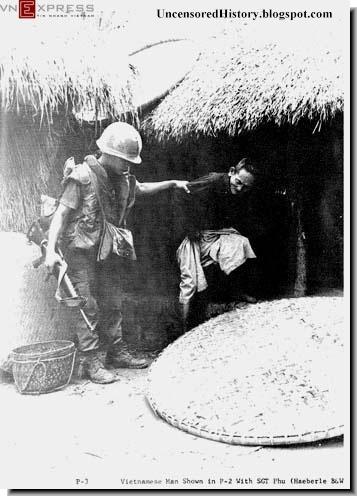

Hunger made German women more "available," but despite this, rape was prevalent and often accompanied by additional violence. In particular I remember an eighteen-year old woman who had the side of her faced smashed with a rifle butt and was then raped by two G.I.s. Even the French complained that the rapes, looting and drunken destructiveness on the part of our troops was excessive. In Le Havre, we'd been given booklets warning us that the German soldiers had maintained a high standard of behavior with French civilians who were peaceful, and that we should do the same. In this we failed miserably. "So what?" some would say. "The enemy's atrocities were worse than ours." It is true that I experienced only the end of the war, when we were already the victors. The German opportunity for atrocities had faded; ours was at hand.

But two wrongs don't make a right. Rather than copying our enemy,s crimes, we should aim once and for all to break the cycle of hatred and vengeance that has plagued and distorted human history. This is why I am speaking out now, forty-five years after the crime. We can never prevent individual war crimes, but we can, if enough of us speak out, influence government policy. We can reject government propaganda that depicts our enemies as subhuman and encourages the kind of outrages I witnessed. We can protest the bombing of civilian targets, which still goes on today. And we can refuse ever to condone our government's murder of unarmed and defeated prisoners of war. I realize it is difficult for the average citizen to admit witnessing a crime of this magnitude, especially if implicated himself.

Even G.I,s sympathetic to the victims were afraid to complain and get into trouble, they told me. And the danger has not ceased. Since I spoke out a few weeks ago, I have received threatening calls and had my mailbox smashed. But its been worth it. Writing about these atrocities has been a catharsis of feeling suppressed too long, a liberation, and perhaps will remind other witnesses that "the truth will make us free, have no fear." We may even learn a supreme lesson from all this: only love can conquer all.

Martin Brech lives in Mahopac, New York. When he wrote this memoir essay in 1990, he was an Adjunct Professor of Philosophy and Religion at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York. Brech holds a master’s degree in theology from Columbia University, and is a Unitarian-Universalist minister.

This essay was published in The Journal of Historical Review, Summer 1990 (Vol. 10, No. 2), pp. 161-166. (Revised, updated: Nov. 2008)