What the Nazis did was downright evil, but what the Allies did as the Second World War ended to Germans and Germany was no less evil. Why were innocent German men, women and children persecuted and thrown out from their centuries' old homes? Was their only fault that a kinky leader and his followers won power through devious compromises in 1933 and then went on to stifle democracy in Germany?

Many say this was war and in war the innocent too suffer.

Does not make sense to me.

After Hitler's war had been lost, millions of ethnic Germans in regions that are today part of Eastern Europe were expelled -- often under horrendous circumstances. It has been proven that at least 473,000 people died as they fled or were expelled. The Nazis' crimes had been far worse, but the suffering of ethnic Germans was immense.

The expulsion of Germans from Eastern Europe was accompanied by large-scale organized violence, including the confiscation of property, placement in concentration camps and deportation - despite the fact that in August 1945, the Statute of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg declared deportation of peoples crime against humanity.

The largest scale expulsion of the Germans occurred in Poland. By the end of the war four million Germans were expelled from the territory of this country . They were mostly concentrated in German territory granted to Poland in 1945: in Silesia (1.6 million people), Pomerania (1.8 million) and East Brandenburg (600 thousand), as well as in areas densely populated historically by Germans in Poland (about 400 thousand). Also, more than two million Germans living in East Prussia, came under Soviet control.

In his comprehensive and dispassionate work Deutscher Exodus (Seewald Verlag), Gerhard Ziemer writes:

|

| German refugees in Berlin. 1945 |

|

| CLICK TO ENLARGE MAP |

One facet of the crucification of the German people was the mass scale driving away of Germans from lands that they lived in for centuries. East Prussia, parts of Poland, Czechoslovakia and other countries.

We have dealt with East Prussia (Hell On Earth) and Czechoslovakia before, but the scale of human misery is such that we felt impelled to look at the ethnic cleansing of Germans again.

The phrase "driving away" is a gross understatement of what the German people endured.

|

| Refugee trek in the Spreewald, 1946. |

Parallel to the large waves of refugees from East Prussia, Pomerania, Brandenburg, and Silesia, began between winter 1944 and summer 1945, the systematic expulsion of the Germans from the formerly occupied territories. In Poland, the Sudetenland, the southern, northern and western border regions of Bohemia (Czechoslovakia), in German "Volga Republic" on Russian territory, in Hungary, Romania (Transylvania, Banat), Croatia (Slavonia), Serbia (Vojvodina ), Slovenia and the Baltic States: The expansionist settlement policy under the Nazi regime had claimed countless victims. Now the resentment of oppressed peoples was discharged against the German civilian population. Hatred and destruction were the answers to the violent crimes of the Nazis. Indiscriminate attacks, killings, summary executions, rape, dispossession, humiliation and repression of the hated Germans occurred . The exodus of the German population was initially only sporadic, later they were systematically expelled from Eastern Europe.

|

| Where the Nazis had settled Germans (CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE) |

The hell on Earth that life became for Germans who underwent ethnic cleansing as Hitlerite Germany was nearing defeat (and after the defeat) has rarely been discussed outside of German-speaking countries. The taint of Nazism has been so severe that the German expellees have been victimized by both journalists and historians. Sinister motives for this phenomenon are unlikely. There has been not so much a concerted conspiracy to withhold the truth, as an embarrassed reluctance to tell it. The passions and confusions of World War II and the Cold War discouraged writers and politicians from defending a group of people who were as powerless as they were despised.

Few in the English-speaking world, even history buffs, know that, as a result of the Potsdam Conference of July-August 1945, millions of Germans lost their 700-year-old homelands in the eastern provinces of Germany and Eastern Europe. The expulsion of Germans from the East, a process that over 2 million did not survive, deserves our attention because of its implications for Europe and for ourselves. The expulsion and its attendant horrors are not overwrought fantasies of German revisionist historians.

The merciless revenge that poured over the entire German civilian population of Eastern Europe, in particular in those sad years of the expulsions from 1945 to 1948 should also awaken compassion, for in either case the common people—farmers and industrial workers, the rich and the poor—all were the victims of politics and of politicians.

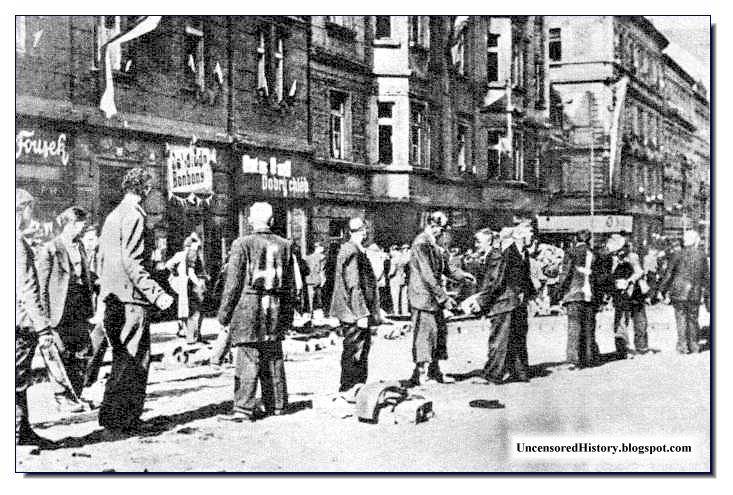

|

| Expelled Germans west of Wroclaw. 1945 |

"There is no question of Germany enjoying any guarantee that she will not undergo territorial changes if it should seem that the making of such changes renders more secure and more lasting the peace in Europe."

Labour MP John Rhys Davies on March 1, 1945 before the House of Commons:

"We started this war with great motives and high ideals. We published the Atlantic Charter and then spat on it, stomped on it and burnt it, as it were, at the stake, and now nothing is left of it."

Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt had discussed the resettlement of populations of Germans or people of German heritage even before the US had officially declared war on Hitler. In the summer of 1941, the two men met on the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales anchored off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, to hash out the details of an Atlantic Charter for a postwar political order.

Once the Nazis had been destroyed, the two leaders decided, self-determination and other rights removed by violent means would be reestablished in Europe. However, there should be no territorial changes that did "not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned."

The Polish and Czechoslovakian representatives were briefly dumbstruck, but then vehemently rejected the very notion. Czech President-in-Exile Edvard Benes, for example, demanded the forcible resettlement of Germans, and even proposed what he called a "painful operation" -- with success. The Allies gave in. They said the charter didn't necessarily apply to Germany. After all, it wasn't a "bargain or contract with our enemies." As early as September 1942, British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden told the Czechs that his cabinet would "agree in principle to resettlement." Meanwhile, Roosevelt indicated to the Poles that he wouldn't object to resettlement.

When the victorious Allies met in Potsdam in the summer of 1945 to lay down the new borders of Europe's nations, Stalin flippantly remarked that there weren't any Germans left in the territories they were handing over to Poland. "Of course not," said US presidential advisor William Leahy to Harry Truman. "The Bolshies have killed them all!"

Final deportation of Germans from Poland was started only after 1949.

WHEN THE RUSSIANS CAME TO EAST PRUSSIA IN 1945.....

NEMMERSDORF

The Testimony Of Emil Radiins, a member of the Volkssturm, or civilian militia, gave the following account:

"On October 23, 1944, just before 8 A.M., I arrived in Nemmersdorf in the company of Regional Commissar Wurach. We had orders to ascertain whether or not people had been shot there. Entering the village from the west, we immediately saw nine bodies lying in a ravine. There were three women, three men and three children, all with head wounds. In the village itself we found a civilian shot dead in front of the fire station; another dead in the cow stall of his barn; a woman sitting in a room with her hands folded, shot dead. Her legs were covered by a comforter, which leads one to believe she didn't even resist or run off when her home was invaded. Her home had obviously been ransacked, everything was a mess. Another woman who had been shot was still crouching next to a wagon parked in the street; she had her hands in front of her face. Near the bridge, in front of a house, an elderly woman lay in the street next to a younger woman and a child. In one house I discovered a young woman whose legs were still spread apart. I remember her now as the same woman whom the doctor had examined, determining that she had been sexually assaulted. In that same room were the bodies of an old man and woman, both with head wounds. We put the bodies in order and carried them to the cemetery"

The rape and killings were part of an unsaid official policy of Stalin to rid East Prussia of Germans. It was annexed soon after the war.

|

| Many ethnic German refugees in the east were herded onto freight trains bound for the west. Scores died from the violence and stress associated with these deportations by trains. |

The first major flood of refugees there began streaming westward in January 1945. In the following months, more than 3 million Germans tried to flee the oncoming Red Army.

When the Soviets and Poles divided the country into five voivodeships, or administrative districts, in March of that year -- again in secret -- the forced resettlement of Germans had already been planned in detail. It began immediately after the cessation of hostilities, first in the new West Poland, and then throughout Pomerania, Silesia, Masuria and the Gdansk region from mid-June onward.

The organizers wanted the resettlement to be "quick and ruthless," though the survivors remember it as more of a "wild expulsion." With the backing of police officers and militiamen, army units encircled the inhabitants in their towns and villages.

"The Germans are to be treated like they treated us," ordered the leadership of the 2nd Polish Army. The aim was to be so "tough and decisive" that the Germans would end up fleeing of their own accord. "The Germanic vermin should thank God they still have a head on their shoulders," boomed one general.

The expulsion applied to all Germans. Poles who had been classified as German citizens under the Nazis' "German People's List" were made to undergo "rehabilitation" procedures. Anyone who was rejected by this process was deported as a "hostile element." A law enacted on May 6, 1945 threatened the death penalty for any Poles who aided such people.

The mass deportation continued until the end of 1946. On Dec. 17 of that year, some 1,800 Germans were chased out of the region in and around the city of Stolp (known today as Slupsk). At 7 a.m. they were told they had until midday to leave the city. One of those affected told the West German parliamentary investigators that most of their luggage was stolen from a courtyard "where a Pole stood with a whip in his hand, wildly lashing out at us." He recalled that some "men and women had to strip naked. Jewelry and valuables were taken off them." The last of the expellees were made to wait at the train station until late at night in temperatures of minus 20 degrees Celsius (-4 degrees Fahrenheit) before militiamen pushed and kicked them onto unheated freight trains.

Many Poles had themselves been driven westward by the Soviets during the Russian occupation of eastern Poland. Some of them therefore sympathized with the hounded Germans, and tried to help. The new administrative chief of Lower Silesia threatened to punish "the use of indiscriminate or excessive cruelty." But this had little impact on the brutality with which the Germans were thrown out.

EXPULSION OF GERMANS FROM CZECHOSLOVAKIA

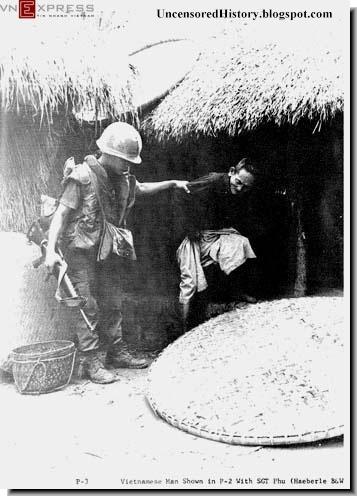

|

| This photo shows an ethnic German woman who had been beaten near Plzen in May 1945 in what was then Czechoslovakia. |

Thousands of Germans living in Prague were interned, robbed and mistreated. Else S., who was held at the country estate of a certain Prince von Lobkowitz, later described how she was forced to work "from early morning into the night" for 13 months. "Food," she said, "was available in the pig troughs. … We were so starving that we even ate the poisoned rodent bate we were supposed to put around the potato sacks. One old man went to get a tin can from the garbage pile and was caught by a guard. We all had to line up and watch as the old man was made to strip to the waist, stand on one leg with his arms raised and shout: We thank our Führer -- all the while he was whipped until, covered with blood, he collapsed."

Armed troops fell upon the Germans in towns like Tetschen (Decin), Aussig (Usti nad Labem), and Königgrätz (Hradec Kralove), killing thousands in the process.

Excuses were easy to find. For instance, when fire broke out at a factory in Aussig, the finger of suspicion was immediately pointed at German saboteurs. Thereupon an armed mob staged a bloodbath in which an estimated 2,000 people -- mostly elderly people, women and children -- were beaten to death, shot or simply flung off the bridge into the Elbe River.

At 9 p.m. on the evening of May 30, 27,000 German inhabitants of Brünn (Brno) were given just ten minutes to dress their children and pack. Armed men then forced them into long columns headed out of the city for a march toward Austria. Women and children were interned on open fields for many months. A writer for Britain's Daily Mail newspaper reported that the field had "become a concentration camp." Such intimidation proved effective: Three-quarters of a million Germans had been chased out of the country even before their expulsion was legitimized at the Potsdam Conference.

|

| Here, American soldiers discover dead and injured Germans on the side of the road after occupying Czechoslovakia's West Bohemia region. |

Shortly before 9 P.M. young revolutionaries of the Czech National Guard marched through the streets calling on all Germans citizens to be standing outside their front doors at nine o'clock with one piece of hand luggage each, ready to leave the town for ever. Women had ten minutes in which to wake and dress their children, bundle a few possessions into their suitcases, and come out on to the pavement. . . . Once outside they had to surrender all jewelry, watches, furs and money to the guardsmen, retaining only their wedding rings. Then they were marched out of town at gun-point to the Austrian border. It was pitch dark when they reached the border. The children were wailing, the women stumbling. The Czech border guards

pushed them over the frontier towards the Austrian border guards. Then more trouble started. The Austrians refused to accept them; the Czechs refused to readmit them. They were pushed into a field for the night, and in the morning a few Romanians were sent to guard them. They are still in that field, which has since been turned into a concentration camp. They have only the food which the guards give them from time to time. They have received no rations. ... A typhus epidemic now rages among them, and they are said to be dying at the rate of 100 a day. 25,000 men, women and children made this forced march from Brno, among them an Englishwoman who is married to a Nazi, an Austrian woman 70-years-old, and an 86-year-old Italian woman.

Not far from Boehmisch-Leipa lies the town of Aussig on the Elbe River (Usti nad Labem). On July 31, 1945, there was an explosion at the cable works. Some Czechs suspected sabotage on the part of the ethnic Germans. A bloodbath followed. Women and children were thrown from the bridge into the river. Germans were shot dead on the street. It was estimated that between 1,000 and 2,500 people were killed.

ALSO READ

Persecution Of Germans In Czechoslovakia, Brno Death Marches

"In eastern Europe now mass deportations are being carried out by our allies on an unprecedented scale, and an apparently deliberate attempt is being made to exterminate many millions of Germans, not by gas, but by depriving them of their homes and of food, leaving them to die by slow and agonizing starvation. This is not done as an act of war, but as a part of a deliberate policy of "peace."

... It was decreed by the Potsdam agreement that expulsions of Germans should be carried out "in a humane and orderly manner." And it is well known, both through published accounts and through letters received in the numerous British families which have relatives or friends in the armies of occupation, that this proviso has not been observed by our Russian and Polish allies. It is right that expression should be given to the immense public indignation that has resulted, and that our allies should know that British friendship may well be completely alienated by the continuation of this policy."

The Relief Commission of the International Committee of the Red Cross reported:

On 27 July 1945, a boat arrived at the West Port of Berlin which contained a tragic cargo of nearly 300 children, half dead from hunger, who had come from a "home" at Finkenwalde in Pomerania. Children from two to fourteen years old lay in the bottom of the boat, motionless, their faces drawn with hunger, suffering from the itch and eaten up by vermin. Their bodies, knees and feet were swollen—a well-known symptom of starvation.

On February 28, 1945, we women of Bledau were separated from our children and transported to the assembly camp at Carmitten. I remained here for about three weeks. During this period we were continually interrogated—they preferred taking us in the night— and during the interrogations we were incessantly beaten and subjected to bestial mistreatment. I'd rather not go into individual torture methods.

After three weeks we were brought to the penitentiary at Tapiau. We sat here behind locked doors and barred windows, shut from the outside world like criminals. At the beginning of March we were loaded onto trains of cattle cars headed for Russia, 48 women in one cattle car. This terrible trip took about four weeks. We ended up in the coalmines of Ruja in the Urals. Besides many other jobs we had to do heavy men's work below ground.

Our guards were Poles who especially "distinguished" themselves in their mistreatment of our men. Getting punched, kicked and hit with a rifle butt was the order of the day.

We lay in underground barracks which were totally infested with bedbugs and lice. In order to get any peace at night we had to get out and sleep in the open air. Up to 40 people a day out of a starting contingent of 2, 000 internees would die of starvation and typhoid fever. The dead were stripped naked and thrown into any open pit. For weeks on end I had to do the wash of the typhoid-infected inmates at the laundry without any disinfectant, almost the whole summer of 1945.

In October 1945, we were taken to a camp named Kistin in the Urals, which was occupied by German and other prisoners of war. All of the remaining women from the first camp were transferred here; there were about 200 of us. I estimate the losses in the first camp at more than 60 %.

After the surrender of the government of Antonescu and the arrival of Soviet troops the new Romanian government refrained from politics of oppression of the German minority. Although in areas densely populated by Germans, a curfew was imposed, and cars, bicycles, radios, and other items considered hazardous were seized from the inhabitants. In Romania there was practically no spontaneous or organized violence against the German population. Gradual deportation of Germans from the country continued until the early 1950s, and in recent years the Germans themselves sought permission to travel to Germany.

2. Der Spiegel

1. After the Reich: The Brutal History of the Allied Occupation by Giles MacDonogh

2. Orderly and Humane: The Expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War By R M Douglas