Red Army attacks Koenigberg. 1945

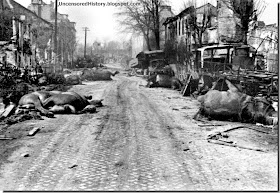

'The city fell in ruins and burned. The German positions were smashed, the trenches ploughed up, embrasures were levelled with the ground,companies were buried, the signal systems torn apart and the ammunition stores destroyed.Clouds of smoke lay over the remnants of the houses of the inner city. On the streets were strewn fragments of masonry, shot-up vehicle sand the bodies of horses and human beings

.'Michael Wieck, A Childhood under Hitler and Stalin

A German paradise called Ost Preussen (East Prussia). Before the Red Army came.

East Prussia. January 1945. The place the Russians entered Germany. What followed was brutal war and an endless nightmare for Germans who had live there for centuries as the vengeful Soviet soldiers let loose retribution for what the Germans had done in Russia for the last few years.....

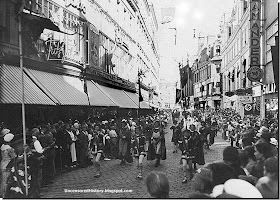

In happier times. Germans parade in Tilsit in 1936

January 1945 was one of the coldest in living memory in north-east Europe. Each night the temperature fell to-25 degrees Celsius and by day it rarely rose above freezing. The ground froze and the Baltic Sea was covered with a solid layer of ice.

On 24 January the advancing Soviet Army severed all road and railway routes to the west and the province of East Prussia was cut off from the rest of the German Reich. In this arctic weather hundreds of thousands of civilians packed their possessions onto sledges and horse-drawn cart sand fled from the Russians.

The German Army was in retreat and the Red Army advanced so rapidly towards the coast that there were only two routes of escape. One was from the Baltic port of Pillau just a few kilometres from Königsberg, where a fleet of vessels waited to transport those who managed to get there to the safety of the west. The other was over a frozen lagoon, the Frisches Haff, beyond which was a narrow sandy spit called the Frisches Nehrung. The Nehrung would lead the refugees to Gotenhafen or Danzig - and to another escape route by sea

On 24 January the advancing Soviet Army severed all road and railway routes to the west and the province of East Prussia was cut off from the rest of the German Reich. In this arctic weather hundreds of thousands of civilians packed their possessions onto sledges and horse-drawn cart sand fled from the Russians.

The German Army was in retreat and the Red Army advanced so rapidly towards the coast that there were only two routes of escape. One was from the Baltic port of Pillau just a few kilometres from Königsberg, where a fleet of vessels waited to transport those who managed to get there to the safety of the west. The other was over a frozen lagoon, the Frisches Haff, beyond which was a narrow sandy spit called the Frisches Nehrung. The Nehrung would lead the refugees to Gotenhafen or Danzig - and to another escape route by sea

German children play in Ashmann Park, Koenigsberg in 1937. Eight years later it was no longer their home.

The German Army had marked out a route with wooden stakes to show where the ice was safe, and thousands of refugees trudged across this pathway.

An eyewitness later recalled the silence of the trekkers as an indescribable ghostly procession with eyes full of misery and wretchedness and quiet resignation. The slow-moving line showed up clearly on the ice and the women, children and elderly people who made up the majority of the refugees were a sitting target for the low-flying Russian aircraft which crossed and re-crossed the frozen waste.

The route was littered with abandoned luggage, upturned carts and the corpses of those who had not finished the journey. Children, the elderly and the sick lay helplessly in open wagons in soaked and freezing straw or under wet dirty blankets. They were the main victims of exposure to the icy weather but many others fell through the ice or were mortally wounded by Russian artillery fire, their blood discolouring the frozen surface of the lake. Their corpses lay all around in grotesque positions. For most refugees, the distant fir-tree-lined Nehrung took two or three days to reach and as the horses grew tired people began to throw goods from their wagons to make them lighter.

An eyewitness later recalled the silence of the trekkers as an indescribable ghostly procession with eyes full of misery and wretchedness and quiet resignation. The slow-moving line showed up clearly on the ice and the women, children and elderly people who made up the majority of the refugees were a sitting target for the low-flying Russian aircraft which crossed and re-crossed the frozen waste.

The route was littered with abandoned luggage, upturned carts and the corpses of those who had not finished the journey. Children, the elderly and the sick lay helplessly in open wagons in soaked and freezing straw or under wet dirty blankets. They were the main victims of exposure to the icy weather but many others fell through the ice or were mortally wounded by Russian artillery fire, their blood discolouring the frozen surface of the lake. Their corpses lay all around in grotesque positions. For most refugees, the distant fir-tree-lined Nehrung took two or three days to reach and as the horses grew tired people began to throw goods from their wagons to make them lighter.

In 1915 during WW1 it was all different. Russian POW in Tilsit with two burly German guards

In the first four months of 1945, 2.5 million East Prussians tried to escape by these routes and it is probable that a million of them died, in the cold, on the ice, in the sea or at the hands of the Russians.

A pretty German girl in East Prussia in the 1930s. One shudders to think what happened to her in 1945....

On 21 January Hans von Lehndorff crossed the large square in front of the Hauptbahnhof and found it overflowing with refugees. There were rows and rows of laden carts and there was a constant flow of newcomers, mainly women. Trains were returning to the station as it was no longer possible to get through to the west and most of the passengers were now determined to escape via Pillau. One woman took him aside to say that she was not worried. 'The Führer won't let us fall into Russian hands,' she said and Lehndorff privately wondered why she still had so much trust.

----------------------

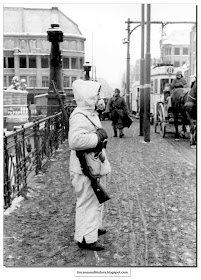

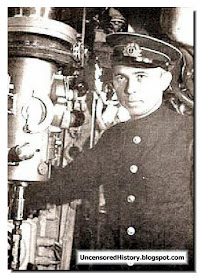

A Soviet officer in Tilsit

August 1944. The Red Army reached the east Prussian border. The sign board says, "That's it, damn Germany."

People began to pack up and leave in haste; women, children and the elderly - the few men who had avoided call-up because of their age or state of health were now mostly fighting with the Volkssturm - all strove to get away from the Russian advance. It was the coldest winter on record and in temperatures of -20 Celsius columns of refugees made their way towards Königsberg and the coast through snowy day sand freezing nights. The refugees, mingling with groups of Allied prisoners of war and freed slave labourers, trudged on foot or rode on farm carts through the bitter weather. Fathers sometimes shot all their families or gave them poison rather than face any more horror.

In the first four months of 1945, 2.5 million East Prussians tried to escape by these routes and it is probable that a million of them died, in the cold, on the ice, in the sea or at the hands of the Russians.

A pretty German girl in East Prussia in the 1930s. One shudders to think what happened to her in 1945....

At 10.00 a.m. on 21 January the church bells of Wehlauwere rung, signalling that all the inhabitants were to leave.Only officials were to remain behind. A couple of trains came through the station on the way to Königsberg but for most there was no room.

The town began to resemble an ant's nest.The streets were completely blocked and the bridges were impassable. There was no time to say goodbye properly to a place which had been East Prussian for 700 years. All they could do was pack a few things and try to get out. Some were lucky and got a lift with the Army but most had to load their belongings on to carts or sledges and struggle through the crowded roads to get to Königsberg or to Samland, where they hoped to find a boat to take them west along the Baltic coast.

The route was so crowded that for many it took twenty hours to go the fifteen kilometres to the safety of the next town, Allenburg. Some tried other routes out of the town to avoid Reichstrasse 1 but on these the refugees were caught by Russian artillery fire and many were killed. Those trying to get to Königsberg were attacked from the air and dead people, animals and broken carts littered the icy roads. Many committed suicide when they ran out of energy.

---------------------The town began to resemble an ant's nest.The streets were completely blocked and the bridges were impassable. There was no time to say goodbye properly to a place which had been East Prussian for 700 years. All they could do was pack a few things and try to get out. Some were lucky and got a lift with the Army but most had to load their belongings on to carts or sledges and struggle through the crowded roads to get to Königsberg or to Samland, where they hoped to find a boat to take them west along the Baltic coast.

The route was so crowded that for many it took twenty hours to go the fifteen kilometres to the safety of the next town, Allenburg. Some tried other routes out of the town to avoid Reichstrasse 1 but on these the refugees were caught by Russian artillery fire and many were killed. Those trying to get to Königsberg were attacked from the air and dead people, animals and broken carts littered the icy roads. Many committed suicide when they ran out of energy.

On 21 January Hans von Lehndorff crossed the large square in front of the Hauptbahnhof and found it overflowing with refugees. There were rows and rows of laden carts and there was a constant flow of newcomers, mainly women. Trains were returning to the station as it was no longer possible to get through to the west and most of the passengers were now determined to escape via Pillau. One woman took him aside to say that she was not worried. 'The Führer won't let us fall into Russian hands,' she said and Lehndorff privately wondered why she still had so much trust.

----------------------

A Soviet officer in Tilsit

Yet even in the first days of January many people in Königsberg still seemed unaware of the true state of the war. No one was allowed to listen to any foreign news and the only information received was what Goebbels was prepared to tell them. His propaganda machine was very efficient and to doubt him was dangerous. Those who remember the last days before the onslaught on East Prussia recall that there were still many who believed the message from Berlin that there was nothing to fear. The propaganda given out day after day was that the German Army was holding the attackers back and that the Russians had been stopped. A few weeks later it became clear that all civilians should have been evacuated to the west when the trains were still running but the authorities did nothing; people went about their day-to-day business in their damaged city and tried to put their fears out of their minds.

August 1944. The Red Army reached the east Prussian border. The sign board says, "That's it, damn Germany."

People began to pack up and leave in haste; women, children and the elderly - the few men who had avoided call-up because of their age or state of health were now mostly fighting with the Volkssturm - all strove to get away from the Russian advance. It was the coldest winter on record and in temperatures of -20 Celsius columns of refugees made their way towards Königsberg and the coast through snowy day sand freezing nights. The refugees, mingling with groups of Allied prisoners of war and freed slave labourers, trudged on foot or rode on farm carts through the bitter weather. Fathers sometimes shot all their families or gave them poison rather than face any more horror.

East Prussia in 1945

The rage of the Soviet soldiers was terrible. There were very few who had not suffered in some way from the Nazi invasion. Most had lost relatives in the war and many had lost their homes and all their belongings under German occupation. The anti-Nazi propaganda of the Soviet Army was so strong that almost every soldier was overwhelmed by an insatiable craving for revenge. The first Germans they met suffered most. Many civilians were indiscriminately killed, women were raped, property was destroyed and German military warehouses plundered.

A defiant German soldier waits for the Russian onslaught late December 1944 in East Prussia.

The vehicles had rolled over people, flattening them in the ice and snow. The houses had broken windows and doors and in the streets were broken china and household goods. The buildings had been completely smashed, houses and barns were half burnt out and some were only a heap of rubble and ash. That was the extent of the material damage. It was what had happened to the people that made us scream and made even the hardest of us retch and be sick and be absolutely petrified. Women had had their clothes slit open. Some were naked. They had been raped and lay on bare floors, or in the street, frozen stiff or dead.There were young girls no more than fifteen or sixteen years old. There were old women; age didn't seem to matter. An old man was nailed upside down on the door of the shed. Along the wall of a house was a row of bodies, all old men and young boys, shot in the back

Erich Koch, the brutal Gauleiter of East Prussia

ERICH KOCH AND EAST PRUSSIA

Koch was appointed as head of the Volkssturm of East Prussia on 25 November 1944. As the Red Army advanced into his area during 1945, Koch initially fled Königsberg to Berlin at the end of January after condemning the Wehrmacht from attempting a similar breakout from East Prussia. He then returned to the far safer town of Pillau, "where he made a great show of organizing the marine evacuation using Kriegsmarine radio communications, before once more getting away himself" by escaping through this Baltic Sea port on April 23, 1945, on the icebreaker Ostpreußen. From Pillau through Hel Peninsula, Rügen, and Copenhagen he arrived at Flensburg, where he hid himself. He was captured by British forces in Hamburg in May 1949.

Erich Koch with Hitler in August 1939

In Königsberg every one's nerves were increasingly on edge for no one knew what was going to happen. The official orders were still that, 'East Prussia will be held; an evacuation is out of the question', and most people now passively accepted the fact that up to this point there had been no orders and no preparations for evacuating civilians. 'We had the impression they would press weapons into our hands so we could fight to prolong the lives of those who had brought all this about in the first place,' wrote Michael Wieck. He recalls how the 'tongue telegraph was working at full speed and not a day went by without more rumours and unbelievable stories of the atrocities of the Russian soldiers.'

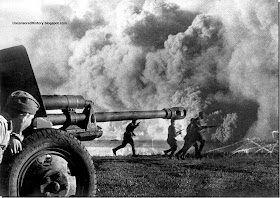

January 13, 1945. The Red Army poised to cross into east Prussia.

A REFUGEE'S ACCOUNT......

The defenders. Highly motivated soldiers of the Gross Deutschland Division with a MG 34 machine gun

A REFUGEE'S ACCOUNT......

"For hours we walked in a herd, measuring time in degrees of hunger, frostbite and exhaustion, and by the gradual dissolution of daylight. Colonies of crows mottled the wintry fields, in which wretches scraped the ground in the hope of finding an unharvested potato, a beet or anything edible. A buzzard kept circling over some dark object, its ghoulish cries sounding like a prophecy of doom. It was difficult to know what was more unnerving - the deep rumbling front approaching from the east or the shuffling and dragging of hundreds of feet over the snow-crusted surface of the road. Night came early - a white and beautiful night, infinitely cold and cruel, in which a full moon dwelled lovingly on the chilling poetry of the naked fields ... And now more people dropped out,collapsing quietly by the road or choosing the deceptive shelter of ditches or hedges for a place to rest, perhaps not realising, perhaps not caring, that they might drift into a sleep from which there was no waking"

The defenders. Highly motivated soldiers of the Gross Deutschland Division with a MG 34 machine gun

When Sybil Bannister arrived in Berlin by train in January 1945 after fleeing the Russians she was startled to find that Berliners seemed to have little idea of what was going on. Apart from the railwaymen, nobody in Berlin had heard that the German defences in the east had collapsed. There had been reports and rumours of the Russian attack but the people still suffered from the delusion that the frontiers of the Reich would be held at all costs.

As far as they knew the trains arriving hour by hour in the city might have been bringing prisoners and not refugees. When the refugees were dealt with, they were treated with contempt and were regarded as scaremongers who, by evacuating the border towns 'unnecessarily', were lowering the morale of good citizens and the armed forces. They would learn soon enough, thought Sybil, when the Russians were on their doorsteps and the tanks began rolling through their streets

Battle for Koenigsberg

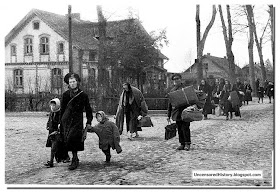

German people fleeing from Pillau. January 26, 1945

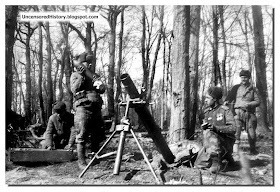

Red Army soldiers bring in the 280 mm Br 5 heavy gun to east Prussia

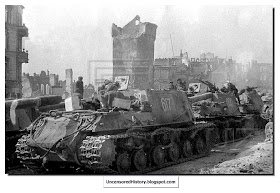

January 1945. Soviet tanks move into Prussia

Destroyed German warplanes in East Prussia. January 16, 1945.

March 1945. Old men from the Volksstrum defend Koenigsberg

At the end of January 1945 Königsberg was packed with 300,000 refugees who had fled to the city hoping it would be the first stop on their flight to freedom. Unable to get any farther, they parked their prams, sledges and carts along the roadsides, crowded into the bombed and damaged buildings and released the horses which had drawn their carts since they left their villages. Many of these animals died of starvation and others were shot; Werner Terpitz recalls how the once beautiful streets were strewn with the carcasses of dead horses from which all edible meat had been taken.

The streets in the town centre were full of rubble made into amateurish road blocks and broken-down trams were abandoned where they had come to a stop. All the city's schools were shut on 23 January and the University closed its doors on 28 January. By 26 January the whole of East Prussia was in Russian hands apart from a strip of land sixty kilometres in length and varying in width, which extended from the southern shores of the Frisches Haff to Königsberg. With Elbing already captured, the encirclement of East Prussia was complete.

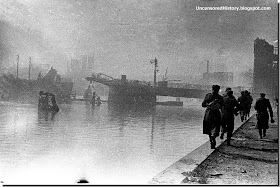

German people fleeing from Pillau. January 26, 1945

Pregnant women had priority on the departing ships, then children and the elderly. Fit and healthy civilian men, though there were few of them, had little chance of being taken for they were to stay to participate in the final defence of the province. Wounded soldiers were also eligible for embarkation - all except the most severely injured whose chances of survival were doubtful or those who were severely mutilated. For them everything was over.

Even by the harbour side the bombardments never ceased and there was almost constant panic among the waiting crowds. These crowds stretched as far as the eye could see trapped on the quayside in front of a large port building which was also crammed with people. Guy Sajer remembers the sound of their thudding feet, like a dull roll of muffled guns, as people stamped to keep themselves warm, and he recalls the solitary children who had lost their mothers whose tears instantly froze as they ran down their cheeks.

Around 450,000 people left Pillau between January and April 1945 in the hope of finding freedom, even though the road route to the port from Königsberg was blocked by the Russians between 26 January and 20 February when the German Army managed to reopen it.

Even by the harbour side the bombardments never ceased and there was almost constant panic among the waiting crowds. These crowds stretched as far as the eye could see trapped on the quayside in front of a large port building which was also crammed with people. Guy Sajer remembers the sound of their thudding feet, like a dull roll of muffled guns, as people stamped to keep themselves warm, and he recalls the solitary children who had lost their mothers whose tears instantly froze as they ran down their cheeks.

Around 450,000 people left Pillau between January and April 1945 in the hope of finding freedom, even though the road route to the port from Königsberg was blocked by the Russians between 26 January and 20 February when the German Army managed to reopen it.

Red Army soldiers bring in the 280 mm Br 5 heavy gun to east Prussia

With Königsberg isolated, Russian planes flew low and unchallenged over the city. If the gunners saw someone move they fired on them, and if they saw a vehicle they bombed it. People began to fear clear mornings because bright blue skies meant the fighters would be lurking. Life in Königsberg became extremely unpleasant. The weather continued to be exceptionally cold, with night-time temperatures as low as-28 degrees Celsius and fuel in short supply. The city was under constant artillery fire. Families had to find what shelter they could underground.

January 1945. Soviet tanks move into Prussia

For the next ten weeks the Russians encircled the city. The outer forts around the city, which had been built at the end of the nineteenth century, remained in German hands,but beyond this ring the Soviet Army entrenched, waiting to pounce. It was a strange time; Germany effectively ended at the rubble wall so hastily built by the volunteers; around it telegraph wires blew about in the wind and from behind came the constant rattle of artillery fire and Russian loudspeakers blaring out propaganda.

There was still water and electricity, and some food supplies for the civilians, refugees and the soldiers bombed out of their units who were trapped in the city. The SS were out looking for men capable of fighting. Many soldiers, who had taken refuge in Königsberg after fleeing from the front,imagined that the Russians would soon break in and had donned civilian clothes and tried to hide from the SS. Terpitz recalls how some were dragged out of their hiding places and were hanged as a deterrent to others:In front of the North Station the corpses lay in the snow day after day with staring eyes. They wore badges which read 'We were cowards and died as a result.

Destroyed German warplanes in East Prussia. January 16, 1945.

Königsberg was one of several towns in the east designated a fortress -Festung- and now Hitler ordered that it must not surrender. Lasch set up his headquarters in an air-raid shelter in the Paradeplatz and from there he attempted to organise the defence of the city. He was short of troops, having at his disposal only four burnt-out divisions including one made up of under-trained Volksgrenadiers. He marshalled soldiers who had taken refuge in Königsberg and incorporated the Hitler Youth into the army.

March 1945. Old men from the Volksstrum defend Koenigsberg

Now we were looking literally at children. Marching beside feeble old men. The oldest boys were about sixteen but there were others who could not have been more than thirteen. They had been hastily dressed in worn uniforms cut for men, and they were carrying guns, which were often as big as they were.They looked both comic and horrifying and their eyes were filled with unease, like the eyes of children at the reopening of school. Not one of them could have imagined the impossible ordeal that lay ahead.

On 20 February the siege of Königsberg was broken. The German Army retook the Samland Peninsula whilst the Königsberg garrison advanced and recaptured the suburb of Metgehen. When the German troops re-entered the area they found that many of the civilian population had been tortured and left for dead.

Later one eyewitness recalled that the Russians had inflicted mass murder on the people of Metgehen: I saw women who were still wearing a noose around their necks that had been used to drag them to death. Often there were several tied together. I saw women whose heads were buried in the mire of a grave or in manure pits whose genitals bore the obvious marks of bestial cruelty.

In the next three weeks, 100,000 citizens and refugees took the opportunity to leave Königsberg for Pillau, via Metgehen. They were under constant Russian bombardment but they knew that from the port boatloads of citizens were being shipped westwards. So many were trying to escape that a temporary camp had to be set up in Peyse on theKönigsberg maritime canal for the people streaming out of the city. There were few facilities and the freezing weather continued; hunger and sickness soon began to plague this temporary camp and some of the escapees tried to return to the city, feeling that at least there they would have some shelter and food. Despite opposition from Party officials, the military were prepared to allow those who wished to return to the city to do so. These returnees swelled the numbers in Königsberg who were to face the Russian onslaught a few weeks later.

Later one eyewitness recalled that the Russians had inflicted mass murder on the people of Metgehen: I saw women who were still wearing a noose around their necks that had been used to drag them to death. Often there were several tied together. I saw women whose heads were buried in the mire of a grave or in manure pits whose genitals bore the obvious marks of bestial cruelty.

In the next three weeks, 100,000 citizens and refugees took the opportunity to leave Königsberg for Pillau, via Metgehen. They were under constant Russian bombardment but they knew that from the port boatloads of citizens were being shipped westwards. So many were trying to escape that a temporary camp had to be set up in Peyse on theKönigsberg maritime canal for the people streaming out of the city. There were few facilities and the freezing weather continued; hunger and sickness soon began to plague this temporary camp and some of the escapees tried to return to the city, feeling that at least there they would have some shelter and food. Despite opposition from Party officials, the military were prepared to allow those who wished to return to the city to do so. These returnees swelled the numbers in Königsberg who were to face the Russian onslaught a few weeks later.

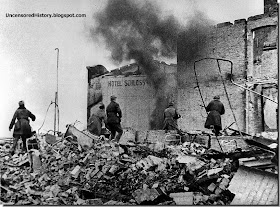

War ravaged Koenigsburg in April 1945 after the encircled Germans finally surrendered after months of brutal fighting.

In Königsberg the lull in the fighting allowed a semblance of normality to return. The bombing and artillery fire stopped and people came out of hiding; social life was resumed. The freezing weather abated in the middle of February and a warm spring breeze blew in from the sea. More and more people came in from the surrounding countryside and the city filled up with both civilians and retreating soldiers. Water, gas and electricity were restored and restaurants and cinemas reopened. Cattle were driven in from the country to provide milk and horses were killed to provide meat. The zoo even began to sell annual season tickets.

A weary cynicism had set in amongst the people who remained in the town. People avoided the word 'military' and spoke less and less about 'army life'. Werner Terpitz recalls how they would simply say the single word ' Barras` (army) making it sound hard and contemptuous. If someone said 'comrade' someone else would say, 'There are no comrades; they all fell at Stalingrad.' When they heard the Germans who had come to live in Königsberg from the Baltic States say, 'We want to make our home in the Reich' (' Heim ins Reich') the response was 'Wir wollen heim, uns reichts' - 'Wewant to go home; we've had enough.'

The young still managed to live from day to day with some optimism but the older people were deeply pessimistic, expecting exile to Siberia or death.Many took refuge in alcohol and took such comfort as they could in their friends as they tried to ignore the deterioration in the city, the rubble, the rubbish, the dead horses, the abandoned trams.

Before the storm broke.... A German soldier stands guard over a bridge in the centre of Koenigsburg

By the middle of March the Soviet Army was preparing for the final assault on Königsberg. The siege was expected to be one of the largest and most difficult urban assaults undertaken by the Soviet Army. Aerial inspections had shown how effective the preparations made in the last few months had been; the powerful forts, innumerable pillboxes and foxholes and well-constructed fortified buildings presented an enormous challenge. The city had three lines of defences;there were fifteen forts on the outer defences, a second line around the suburbs and another defensive line protected the inner city.

By the middle of March the Soviet Army was preparing for the final assault on Königsberg. The siege was expected to be one of the largest and most difficult urban assaults undertaken by the Soviet Army. Aerial inspections had shown how effective the preparations made in the last few months had been; the powerful forts, innumerable pillboxes and foxholes and well-constructed fortified buildings presented an enormous challenge. The city had three lines of defences;there were fifteen forts on the outer defences, a second line around the suburbs and another defensive line protected the inner city.

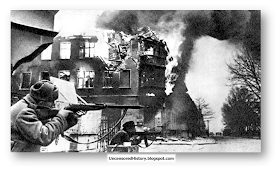

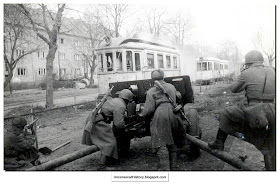

Bitter fighting in Koenigsburg

The Red Army now turned its attention again to Königsberg and towards the end of the month low-flying Russian aircraft began blaring out messages to the people of Königsberg: 'Men of the Volkssturm go home! We won't hurt you, you old granddads. Throw your rifles away.' Whenever the weather was clear their planes strafed the city and artillery fire increased steadily.The preliminary bombardment began at the very beginning of April but the weather was poor, and fog and rain impeded pilots and gunners. April 1 was quiet but the next day the Russians began to use heavy artillery against the outer forts and pillboxes. On 4 April many listened to the news on the radio for the last time - then the electricity went off as the artillery bombardment grew in intensity.

Russian artillery fires on the streets of Koenigsburg

Thursday 5 April 1945 was a beautiful warm spring day and the Russians used the clear blue skies and the sunshine to fly low above the city, dropping bombs as they went. Wave after wave of aircraft came over. Hans von Lehndorff observed that there was no response from the German armed services. 'We felt as if we were sailing on an ocean in a sinking ship,' he wrote."

The Soviet planes flew over undisturbed and attacked wherever took their fancy. A black pall of smoke hung over the inner city and floated up into the translucent sky. More than a hundred planes were in the sky at a time,most only 500 metres above the ground, so that they could deliberately aim at people in the streets. That day Werner Terpitz and his battalion were sent to defend the western edge of the city but it was already too late.

Fortress Königsberg was indefensible.The assault on Königsberg began the next day, at 7.30 a.m.on 6 April 1945. It began with the relentless shelling of the city by thousands of guns, mortars and rocket launchers,followed by yet more aerial bombardment. An eyewitness recorded: The city fell in ruins and burned. The German positions were smashed, the trenches ploughed up,embrasures were levelled with the ground, companies were buried, the signal systems torn apart and the ammunition stores destroyed. Clouds of smoke layover the remnants of the houses of the inner city. On the streets were strewn fragments of masonry, shot-up vehicles and the bodies of horses and human beings.

As the Russians smashed through vital sections of the perimeter of the city, Lasch became convinced that the end was inevitable. Wave upon wave of air attacks passed over the city, which sank into burning ruins; not one German fighter plane was available to help resist the aerial bombardment.The German positions were crushed and the defenders' foxholes were overrun. Entire companies were buried and ammunition dumps were blown up.

Both the Army and the Volkssturm were desperately short of equipment. They lacked weapons, ammunition and trained personnel to tell them what to do. On the streets the lack of anti-aircraft defence meant that there was a constant danger of being killed by the dive-bombers. Clouds of smoke hung over the city; the streets were littered with rubble and corpses; and terrified civilians fled from their bombed and burning houses, attempting to save whatever possessions they could.

A survivor remembers with horror that:[The] Russian barrage on Königsberg was incredible. Even the old stagers had never seen anything like it. The youngest kids who were with us in the trenches screamed 'Help' and 'Mum' and the infantrymen were howling and bawling 'Get those kids out of the trenches.' It was a shambles.

The landmark of Koenigsberg, the Green Bridge in 1945

The death struggle for Festung Königsberg was now at its height. The city was attacked by thousands of artillery weapons and squadrons of bombers circled endlessly,destroying everything they hit in, as Michael Wieck puts it,'that wretched city'. Clouds of smoke hung over the town as chunks of buildings were sent flying through the air and cars were riddled with bullets. The Volkssturm was breaking apart and the wounded and the dead were piling up all over.

Frightened civilians fled from the Russian infantry and tank corps; by the evening of 6 April 1945, Russian soldiers were already well into the city. Assault units had pushed their way in, blowing up several forts, cutting the Königsberg-Pillau railway line and piercing the defensive system. 'When I went outside,' wrote Hans von Lehndorff, 'the town was crawling with Russian soldiers with strange wild faces and the town was on fire.' The attack continued throughout the night.

A destroyed German Stug 3

By the morning of 7 April, with the sound of battle at its height, Königsberg was covered in a thick pall of smoke, but this did not prevent more aircraft sweeping in to bomb yet more of the city. Some 246 bombers carried out three waves of attacks whilst ground troops made their way forward, street by street. They used 'Stalin organs', rocket launchers mounted on the backs of trucks, which could fire off rapid concentrated barrages.

The number of German dead and wounded began to mount and the medical services could not cope. People began to hang white sheets out of their windows in the hope of bringing the conflict to an end before more lives were lost.On 8 April the Russians crossed the Pregel by boat, cutting off central Königsberg completely. Deputy Gauleiter Grossherr and the remaining Party personnel agreed that Königsberg was doomed and called on the military to organise a mass escape to Samland. Now, when it was all too late, enormous efforts were made to get people away with military help. General Lasch remembers how:]Local knowledge ceased to be of any help in the inferno, which had once been the city of Königsberg.

Ghostly lunar landscapes had come into being in place of the great avenues which used to lead through the city. Paths could be reconnoitred and just an hour later they were impassable; the remaining façades of the buildings collapsed into the streets and the ground was torn up by mighty bomb craters. About ninety per cent of the city was now destroyed.

The confusion was compounded when, at just after midnight on 9 April, the Party authorities, without reference to Lasch, passed the word for the civilian population to assemble on the old Pillau road. The people set off at 2.00 a.m. in a huge swarm. The Russians noticed and swamped the area with fire. The result was a bloodbath and heart-breaking scenes were played out as survivors tried to drag themselves back to their homes.

The Soviet 11th Guards Army soldiers fire mortars near Pillau

A dejected German soldier in east Prussia in 1945. An image that described well how the Wehrmacht was feeling in 1945.

The surviving weary and desperate 4000 soldiers of the Gross Deutschland Division arrive in Pillau from Balga. They defended Pillau till April 25, 1945 when they were overrun by the overwhelming Red Army

Daylight showed a city in ruins, enveloped in a cloud of smoke. Thousands were injured and the first-aid stations were overrun with people needing emergency treatment.The Russians were everywhere and treating the wounded became more and more difficult, as the attackers ransacked every building they came to, searching for valuables like watches and other treasures.

On the morning of 9 April, Hansvon Lehndorff, still working in the first-aid station where he was a doctor, was woken by the sound of Russian troops demanding that everyone should hand over their watches.The one German word they knew was watch -Uhr' - and they trampled over the wounded shouting 'Ur, Ur, Ur'. When they found none, one of the soldiers stuck three fingers in the air and swore that if no one would give him a watch three people would be shot.

The Russians had a saying: 'The first wave gets the wrist watches, the second wave gets the girls and women, the third wave gets what is left,' and these young soldiers were in the first wave.

A dejected German soldier in east Prussia in 1945. An image that described well how the Wehrmacht was feeling in 1945.

That day General Lasch accepted that the situation was hopeless and contacted the Russian high command, who guaranteed good treatment. The surrender finally came on the evening of 9 April 1945 at 9.30. Hitler declared Lasch a traitor, sentenced him to death and ordered the arrest of his family. At the time of the surrender there were in the city between 30,000 and 35,000 soldiers, 15,000 foreign workers and more than 100,000 civilians

The surviving weary and desperate 4000 soldiers of the Gross Deutschland Division arrive in Pillau from Balga. They defended Pillau till April 25, 1945 when they were overrun by the overwhelming Red Army

Russian soldiers swept the ruins looking for Nazis and surviving German soldiers were marched off to captivity in the labour camps whilst the Red Army troops plundered the city, burned, robbed, drank and raped. The intention was clearly to terrorise the remaining civilians; women's voices could be heard crying out 'Shoot me, shoot me' as they begged for mercy, and many shot or poisoned themselves to avoid the rage of the Russian soldiers. Many members of the Volkssturm who had survived the fall of their city were murdered.

The German ship 'Wilhelm Gustloff' in 1939. The Wilhelm Gustloff′s final voyage was during Operation Hannibal in January 1945, when it was sunk while participating in the evacuation of civilians, military personnel, and Nazi officials who were surrounded by the Red Army in East Prussia. The Gustloff was hit by three torpedoes from the S-13 in the Baltic Sea under the command of Alexander Marinesko on the night of 30 January 1945 and sank in less than 45 minutes. An estimated 9,400 people were killed in the sinking, possibly the largest known loss of life occurring during a single ship sinking in recorded maritime history

THE TRAGEDY OF WILHELM GUSTLOFF

THE TRAGEDY OF WILHELM GUSTLOFF

On 26 January thousands of refugees waiting on the quayside at Pillau were killed when the ammunition depot was blown up. Then, just a few days later, on 30 January 1945,the largest passenger shipping disaster in history - far worse than the Titanic - occurred outside the port of Gotenhafen.Gotenhafen was a collection point for both civilians and wounded soldiers and thousands were awaiting transport on the quayside. One of the ships available to transport them was the Wilhelm Gustloff.

The Nazis had built the Wilhelm Gustloff in the 1930s as a cruise liner, but when war broke out it was used as a hospital ship, ferrying casualties across the Baltic. On that night 60,000 people were waiting to escape from Gotenhafen and, as soon as the gangplanks were put in place, the desperate escapees tried to push their way on board. In the event 1,100 crew, 730 wounded soldiers, 373 young women who belonged to the Women's Naval Auxiliary and more than 6,000 civilian refugees, mostly women and young children, were packed into the ship - a total of over 9,000 people.

More than 30,000 of the people were trying to escape back to Germany by sea in four liners. Bound for a port near Hamburg, the convoy was just rounding the Hela Peninsula and leaving the Gulf of Danzig for the Baltic Sea. The biggest of these ships, the 25,000-ton Wilhelm Gustlofl, had never before carried so many passengers-1500 young submarine trainees and some 8000 civilians—eight times the number on the Lusitania. No one knew exactly how many frantic refugees had boarded at Danzig. Though everyone was supposed to have a ticket and evacuation papers, hundreds had smuggled themselves aboard. Some men hid themselves in boxes or disguised themselves in dresses. Refugees had been known to go to even more shameful extremes to escape the Russians.

Only 950 were saved by the rescue ships. Over 8000 perished in the greatest of all sea disasters-more than five times the number lost on the Titanic.

Recently at Pillau, where only adults with a child were allowed to board a refugee ship, some mothers tossed their babies from the decks to relatives on the dock. The same baby might be used as a ticket half a dozen times. In the frenzy some babies fell into the water, others were snatched away by strangers. As the Wilhelm Gustloff headed west into the choppy Baltic, a middle aged refugee, Paul Uschdraweit, came on deck. He was one of the doughty district officials of East Prussia who had defied Gauleiter Koch and let his people evacuate their towns. He himself had barely escaped the Red Army advance with his chauffeur, Richard Fabian.

The rest of the convoy was skirting the coast of Pomerania to avoid Russian submarines, but the Wilhelm Gustloff drew too much water and was on its own, except for a lone mine sweeper. Uschdraweit looked for the other ships of the convoy but could only see the mine sweeper, a mile away. He was glad he’d had the foresight to check the ship for the best exit in case it sank. Just then the ship’s captain announced over the loudspeaker that men with life belts must surrender them; there weren’t enough for the women and children. No radios would be turned on, no flashlights used. The Baltic was rough, and most of the women and children became violently seasick.

Since it was forbidden to go to the rail, the stench soon became intolerable. The sick were brought amidships, where the pitch was less violent.

The ship steamed westward, twenty-five miles off the Pomeranian coast. A number of lights were still on, outlining the Wilhelm Gustloff sharply against the dark Baltic. At 9: 10 P.m. Uschdraweit was wakened by a dull, heavy explosion. He was trying to remember where he was when he heard a second roar. Fabian, his driver, rushed past, ignoring his shouts. Then came a third explosion, and the lights which should have been extinguished earlier went out. Off the port side lurked a Russian submarine, waiting to put a fourth torpedo into the liner if necessary—or to sink any ship that came to the rescue.

More than 30,000 of the people were trying to escape back to Germany by sea in four liners. Bound for a port near Hamburg, the convoy was just rounding the Hela Peninsula and leaving the Gulf of Danzig for the Baltic Sea. The biggest of these ships, the 25,000-ton Wilhelm Gustlofl, had never before carried so many passengers-1500 young submarine trainees and some 8000 civilians—eight times the number on the Lusitania. No one knew exactly how many frantic refugees had boarded at Danzig. Though everyone was supposed to have a ticket and evacuation papers, hundreds had smuggled themselves aboard. Some men hid themselves in boxes or disguised themselves in dresses. Refugees had been known to go to even more shameful extremes to escape the Russians.

Only 950 were saved by the rescue ships. Over 8000 perished in the greatest of all sea disasters-more than five times the number lost on the Titanic.

Recently at Pillau, where only adults with a child were allowed to board a refugee ship, some mothers tossed their babies from the decks to relatives on the dock. The same baby might be used as a ticket half a dozen times. In the frenzy some babies fell into the water, others were snatched away by strangers. As the Wilhelm Gustloff headed west into the choppy Baltic, a middle aged refugee, Paul Uschdraweit, came on deck. He was one of the doughty district officials of East Prussia who had defied Gauleiter Koch and let his people evacuate their towns. He himself had barely escaped the Red Army advance with his chauffeur, Richard Fabian.

The rest of the convoy was skirting the coast of Pomerania to avoid Russian submarines, but the Wilhelm Gustloff drew too much water and was on its own, except for a lone mine sweeper. Uschdraweit looked for the other ships of the convoy but could only see the mine sweeper, a mile away. He was glad he’d had the foresight to check the ship for the best exit in case it sank. Just then the ship’s captain announced over the loudspeaker that men with life belts must surrender them; there weren’t enough for the women and children. No radios would be turned on, no flashlights used. The Baltic was rough, and most of the women and children became violently seasick.

Since it was forbidden to go to the rail, the stench soon became intolerable. The sick were brought amidships, where the pitch was less violent.

The ship steamed westward, twenty-five miles off the Pomeranian coast. A number of lights were still on, outlining the Wilhelm Gustloff sharply against the dark Baltic. At 9: 10 P.m. Uschdraweit was wakened by a dull, heavy explosion. He was trying to remember where he was when he heard a second roar. Fabian, his driver, rushed past, ignoring his shouts. Then came a third explosion, and the lights which should have been extinguished earlier went out. Off the port side lurked a Russian submarine, waiting to put a fourth torpedo into the liner if necessary—or to sink any ship that came to the rescue.

From The Last 100 Days: The Tumultuous and Controversial Story of the Final Days of World War II in Europe by JOHN TOLAND

Alexander Marinesko: The Soviet Navy submarine commander who ordered the torpedoing of Gustloff

Every last centimetre of space was taken. The temperature outside was -10 Celsius, it was snowing and the deck was covered with layers of ice. The ship was unescorted and, because the visibility was poor, the captain decided to sail out into the open sea rather than keep to coastal waters. At 9.10 p.m. a Russian submarine, which was off course because the captain had disobeyed orders, spotted the Gustloff. Four torpedoes were fired and three direct hits were made below the waterline.

The thousands on board began to panic, with everyone pushing to get up on deck. They clawed their way upwards; children slipped from their mothers' arms and were crushed. The ship was sinking fast and many of the lifeboats were under water before they could be launched.Others were covered with such a thick layer of ice that they were too heavy to launch. It soon became obvious that the majority on board were doomed.

The ship sank just fifty minutes after being hit and the water was so cold that no one could survive for more than a few minutes. Of the 9,000 people on board only 996 survived.

Germans surrender in Koenigsburg

After Königsberg had fallen, the Soviet Army turned its attention to Pillau, which was fanatically defended by the Germans following orders which went out to hold the port at all costs in order to permit every available German ship to take off refugees and soldiers. Some 20,000 German troops fought furiously for six days, inflicting enormous damage on the Russians but with huge casualties on their own side. The Germans finally surrendered Pillau on 26 April 1945. As the war came to an end, the evacuation by ship of Army Group North stranded in Kurland also began. In an operation reminiscent of Dunkirk every available vessel, from mine-sweepers to trawlers, ran a shuttle service from tiny ports strung along the Kurland coast and took the soldiers to bigger harbours for evacuation to the likes of Kiel and Eckernförde

German civilians in Koenigsburg

Koch had abandoned East Prussia and Königsberg and those who remained now faced the wrath of the Russians.The German armed forces had slaughtered indiscriminately in Russia and Eastern Europe and now it was the turn of the Red Army to exact its own revenge. Drunk on the alcohol they found in the town, Russian soldiers killed old men, raped women and set on fire what remained of the city. They ransacked cellars where people were hiding and destroyed the houses above their heads. They herded groups of people together and shot them; they stormed the hospitals and threw the sick and wounded out of the windows. People remember cemeteries being destroyed, gravestones ripped up, and coffins flung open. Anyone suspected of being a Nazi was rounded up and sent to a labour camp.

German soldiers in Koenigsberg surrender after the Soviet army stormed it on April 9, 1945

Not much is known about the eventual fate of the Königsbergers who were forced to stay in the city. Many committed suicide and those who hung on through the next few months, hoping for a return to normality which was never to come, were pre-occupied with finding enough food to live on. With no proper government in place a poorly disciplined army was left in charge of the city.The Russians made no attempt to supply the German survivors with provisions. In an echo of what the people of Leningrad had had to endure when the Germans besieged their city, the people of Königsberg lived on the verge of starvation, amidst unburied corpses, non-existent sanitation, polluted water, disease and terrible infestations of flies. Stray dogs roamed the streets and anything that could be caught - cats, dogs, rats - ended up in the stew pot. On the brink of starvation and without fuel, survivors remember searching the gardens and fields for sorrel, dandelions and stinging nettles to boil into soup over fires made of sticks, seemingly unaware that the Germans had subjected the people of Leningrad to far worse. There was no electricity and even the polluted water supplies often failed.

The contrast. German holiday crowds in Koenigsberg in 1935.

A SAD END TO A ONCE THRIVING GERMAN KOENIGSBERG

The Russianisation of Königsberg began even before the final surrender on 8 May 1945. Loudspeakers were installed on every corner which blared out Russian music. Within a few days of the fall of the city, direction signs and place names in German were torn down and replaced by new ones in Russian script.

As Russians arrived in the town, those Germans who still had somewhere to live were turned out of their homes and forced to find shelter in bombed-out cellars without heating, lighting or water.In the winter of 1945-6 there were rumours of cannibalism and in the summer of 1946 there were outbreaks of typhus,malaria and typhoid, caused by drinking water from artificial lakes (built by the Nazis to double the water supply) being filled with decaying corpses and garbage. There were terrible infestations of lice and rats. The only proper food available,apart from a small allowance of bread given to those Germans who were given jobs by the Russians, was rye grain from fields in the surrounding countryside that had not been harvested in the summer of 1945 and had regrown a season later.

Of those who stayed behind, it is thought that half died in the course of the first three months after the surrender and another twenty-five per cent in the next three years. Michael Wieck believes that the Russians '... intentionally destroyed every resource needed for survival and thwarted every attempt people made to look after themselves, as if they wanted to accelerate the rate at which Königsbergers died.'And this was because, 'In their hearts they carried the pain of millions and millions of fallen comrades, starving civilians and murdered relatives and friends.'

In July 1946 northern East Prussia and Königsberg, an area about half the size of Belgium, officially became part of the Soviet Union after the signing of an agreement at the inter-Allied Potsdam Conference, which met in July and August 1945. The rest of East Prussia would go to Poland; Memel and the surrounding countryside became part of Lithuania.Königsberg and its environs were collectively renamed the Kaliningrad Oblast (region) in July 1946 (after Mikhail Kalinin, one of Stalin's cronies who had just died) and it was declared a military zone.

A barbed-wire fence was erected along its entire border with Poland, dividing families and communities. The first Soviet settlers arrived that summer from many parts of Russia, and East Prussia started to become Russian. Banners displaying the faces of Stalin,Lenin, Marx and Kalinin appeared all over the remains of the city and loudspeakers played Russian music. The port of Pillau was renamed Baltiysk and became home to the Soviet Baltic Fleet. It is still closed to foreigners and is the only Russian Baltic port which is ice-free for most of the winter.During the Cold War there were at times up to half a million troops stationed in the Kaliningrad region although there have been fewer since the end of the Cold War.

Koenigsberg broken. April 9, 1945. After the Germans surrendered. Russian officers with the Steindammer wall in the background.

Koenigsberg in April, 1945. A city devastated.

Koenigsberg in April, 1945. A city devastated.

General Otto Lysh, the German officer in defence of Konigsberg after he signs the surrender on April 9, 1945. He observed, " I never thought that a first-rate fortress like Konigsberg would fall so soon under the blows of the Soviet army."

German people watch helplessly as a Red Army tank trundles on a street in Konigsberg in 1945

Port town of Pillau. The Germans evacuated on April 25, 1945

Nightmare in East Prussia. German refugees fleeing their land in Grantsa District in April 1945. The Allies had determined that Germany was to lose East Prussia and the Germans there were to be expelled westwards.

The rag-tag Red Army soldiers celebrate the German surrender. East Prussia. May 1945.

East Prussia Today: Remains Of A Day

Suggested Reading

FALL OF HITLER'S FORTRESS CITY: The Battle for Konigsberg 1945

By ISABEL DENNY

-------------------------------------

Battleground Prussia: The Assault on Germany's Eastern Front 1944-45

By Prit Buttar

By ISABEL DENNY

-------------------------------------

Battleground Prussia: The Assault on Germany's Eastern Front 1944-45

By Prit Buttar